Who’s responsible for public records?

Amador County lies west of the Sierra Nevada mountains, in California’s historic Gold Rush territory.

Here in the small town of Ione, Jewel Jackson owned two rental homes.

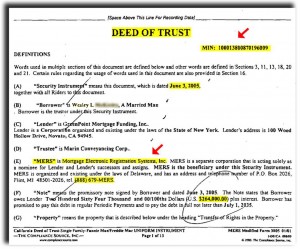

In March 2007, while she was living in Texas, Ms. Jackson’s brother Willie B. Norton determined to take control of her properties without her knowledge. To this end, Norton crafted a power of attorney purporting to appoint himself as Ms. Jackson’s attorney in fact to conduct real estate transactions on her behalf.

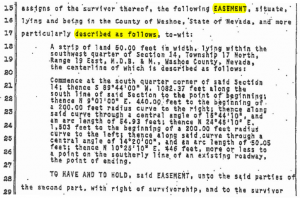

This was amateur hour. Norton alone signed the power of attorney form, before getting it notarized and recorded. Then he signed two quitclaim deeds transfering the properties to himself, and likewise had them notarized and recorded. When the paperwork was done, he evicted Ms. Jackson’s tenants.

Crime as inartful as this did not fool the authorities. Norton was prosecuted, and he pleaded guilty.

In the meantime, Ms. Jackson’s loss of rental income caused her to miss mortgage payments and the properties were lost to foreclosure.

So it happened that Ms. Jackson sued the County for negligently recording the sham documents. She argued the power of attorney was obviously bogus, since it wasn’t signed by the person supposedly granting the power. As such, it should not have been accepted by the recorder’s office and should not have appeared in the land records.

In its defense, the County said the documents were “recordable,” since they were on required sized paper (81/2 x 11), were legible, and were notarized.

The trial court agreed with the County, and Ms. Jackson appealed.

The Court of Appeals also sided with the County, saying the recorder was, in fact, legally required to record these documents because they were in proper format. Likewise, the Court said, the recorder is not responsible for legal sufficiency of recorded documents, and to hold otherwise “would place a county recorder’s office in the untenable position of requiring its employees to in effect practice law.”

Moral: Aside from the limited protection of notary laws, no one really vouches for validity of what gets into public land records.

Title insurance covers a multitude of risks for owners and lenders, and policies offered in some markets may in fact cover post-policy forgery. It’s a good idea to know your insurance coverage, before and after investing in real property.

The case is Jackson v. County of Amador, 186 Cal.App.4th 514 (Cal. App. 2010).