Where there’s a will, there’s a way.

ATLANTA, GA–For many years until her death in 2005, this was the home of Amanda Jones.

Among her close relations, Ms. Jones had a niece named Lillie Mae Walker. In 1976, Ms. Walker came to live with Ms. Jones. Later, in 1994, Ms. Walker’s daughter, Laurlene Riggins, also moved in. Ms. Riggins provided care for Ms. Jones, who was then 90, and Ms. Walker, then 72.

In 1995, Ms. Jones signed a Last Will and Testament giving a life estate in the property to Ms. Walker, with the remainder interest going to Ms. Riggins.

Ms. Jones had a stepson, named Eugene. In June 2003, she signed a different Last Will and Testament in which she bequeathed the property to Eugene. But then, in October 2003, Ms. Jones signed yet another Last Will and Testament, revoking all previous wills and again bequeathing the property to Ms. Walker as to a life estate, with the remainder going to Ms. Riggins.

Ms. Jones died in April 2005. After her death, Ms. Walker and Ms. Riggins continued to live in the home–but they neglected to file the October 2003 will for probate.

Enter Ellene Jones, Eugene’s wife. In May 2005, Ellene filed the June 2003 will for probate. Without notice to Ms. Walker or Ms. Riggins, the Probate Court named Ellene executrix of Ms. Jones’ estate and, in July 2005, Ellene executed a deed transferring the ‘free and clear’ property to Eugene.

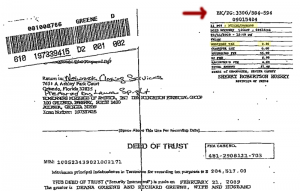

Eugene promptly mortgaged the property, giving a security deed (akin to a deed of trust) to Ameriquest, for $95,500, in August 2005. Ameriquest got a drive-by inspection, never speaking to residents Walker and Riggins.

Ms. Riggins learned of the mortgage in mid-2006, after getting a mortgage-related notice in the mail followed by telephone calls, but Eugene denied any knowledge of it.

So Ms. Riggins got a lawyer, and filed the October 2003 will for probate. The Probate Court revoked Ellene’s appointment, and approved the October 2003 will as Ms. Jones’ true Last Will and Testament. Ms. Riggins was made the new personal representative of the estate, whereupon she deeded property to herself and Ms. Walker.

The stage was set for a legal battle between the heirs and the lender (now Deutsche Bank). The lender sued to quiet title, and the trial court ruled for the lender. The heirs appealed.

The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed the trial court decision. The high court explained that, under Georgia statutes, an innocent purchaser of property from an ‘apparent’ heir of a deceased person is protected “as against unrecorded liens or conveyances.”

The Court reasoned that the lender did not have “actual notice” of the true heirs’ interests because Walker and Riggins had not opened a probate at the time the loan was made. And, the Court said, the lender would not be charged with knowledge it could have gained from parties in possession, but instead acted reasonably in relying on what Eugene told them–which was, “momma…made the will to me” but Ms. Walker “is supposed to live there until she dies.”

The Court concluded, “Ameriquest’s failure to inquire further regarding Walker’s status in the house does not show a lack of good faith.”

Moral: In light of this harsh result, seems the Georgia legislature should do some work on its statutes.

But the real moral here is that anyone with an interest in property under a will should see that the will is promptly probated. Failing to act is risky business.

The case is Riggins v. Deutsche Bank, 708 S.E.2d 266, 288 Ga. 850 (Ga. 2011).